By Mark Dursin

“Words and music.”

Those three words (accompanied by a “fingers crossed” hand gesture) was Eddie Wilson’s mantra in the 1983 film Eddie and the Cruisers. For Eddie, those three words summed up the magic that happens when just the right lyric matches up with just the right melody.

In the film, shy lyricist — and future English teacher — Frank “Wordman” Ridgeway (Tom Berenger) provides the poetry, which Eddie (Michael Pare) brings to life with his unique brand of mid-60s rock-and- roll (which sounds suspiciously like early-80s John Cafferty). Now, although Wordman and Eddie are fictional, the 1980s saw some inspired real-life collaborations (as well as some less-than-inspired ones . . . I’m looking at you, Rick James and Eddie Murphy).

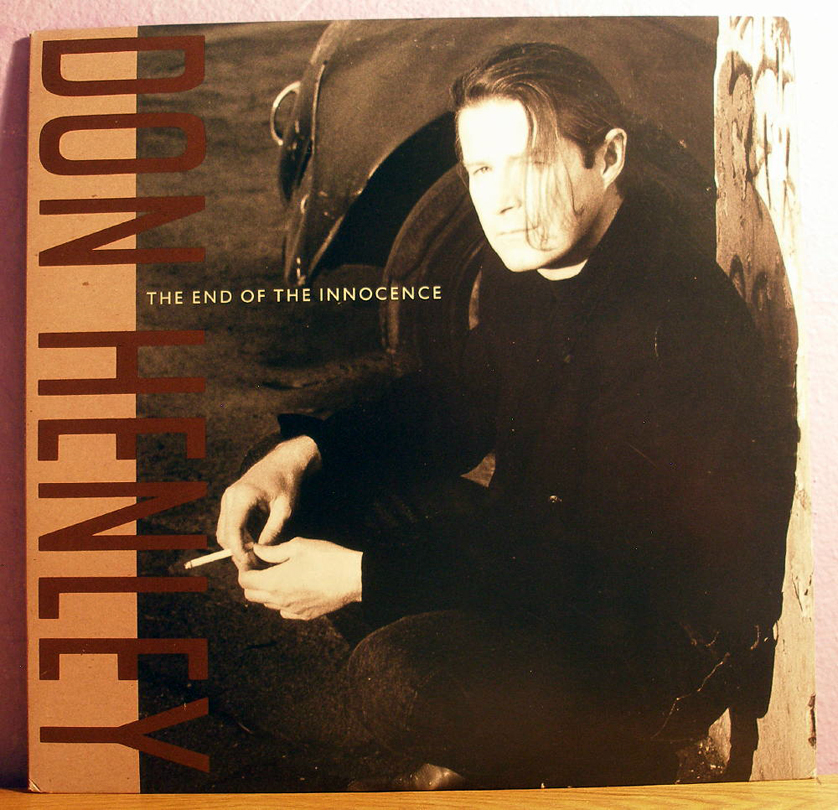

But for my money, one of the best example of the “words and music” synergy happened at the very end of the decade, twenty-five years ago, in the summer of 1989. Yes, the summer when Harry met Sally was also the summer that Don met Bruce — that is, the summer Don Henley and Bruce Hornsby released “The End of the Innocence.”

The collaboration actually started two years before, in the summer of 1987, when Hornsby got a surprise phone call from Henley. At the time, Hornsby was what an Eagles-era Henley might have called “the new kid in town”: Bruce’s “The Way It Is” thrust him into the spotlight in late ‘86, and he earned a Grammy for Best New Artist in 1987. Henley didn’t know Hornsby personally, but he was hoping they could work together, so they arranged for Henley to come over to Hornsby’s house in the San Fernando Valley.

There’s no road map for collaboration. For example, most of the classic Bernie Taupin-Elton John songs started with words; Taupin wrote the lyrics first, then Elton put music to them. For “The End of the Innocence,” the music came first: Hornsby played for Henley a track for a song that he had tried to write, but he just couldn’t get the right words. But Henley could; as he drove home from Hornsby’s house, Don re-listened to a cassette of the abandoned song and called Hornsby down the road. He had something.

As far as what that “something” turned into . . . hey, this is Don Henley we’re talking about! Of course, the lyrics are going to be brilliant! But what makes “The End of the Innocence” stand out, even when compared to other Henley songs, is how layered it is. While the song is called “The End of the Innocence,” it maybe should be called “The Ends of the Innocence,” because there are, my by count, four “endings” in this song. Briefly:

First verse: Your standard “end of childhood,” the Holden Caulfield-esque fall from grace that inevitably happens when you realize Santa isn’t real, your parents make mistakes, and that life isn’t as rosy as you once thought.

Second verse: Henley expands his scope, from a personal loss of innocence to a national loss. A child of the 60s, Henley was disillusioned how the country lost its sense of idealism in the 80s, as people started focusing solely themselves. Along the way, he gets in some veiled shots at President Reagan (the “tired old man that we elected king”).

Third verse: Here, he goes back to the personal, comparing the inevitable “loss of innocence” to the eventual end of a relationship. Henley seems to be reflecting on the idea that all relationships end: someone leaves, someone dies, people drift apart. All we can do is hold on to the memories. (“I need to remember this,/ So baby give me just one kiss.”.)

Pre-Chorus and Chorus: This “loss” connects to a theme that runs throughout Henley’s work and life, from the song “The Last Resort” to his founding of the Walden Woods Project: the steady destruction of the natural world.

This one may require some background: In his book To The Limit, author Marc Eliot talks about how Henley, while driving to Hornsby’s house for the first time, passed by a cornfield, “one of the last stretches of underdeveloped land” in the San Fernando Valley. The image seemed to resonate with Henley the Environmentalist; in the song, the narrator is inviting someone (maybe the lover in the third verse) to go to a place “still untouched by men.” But the chorus seems to suggest that men WILL eventually touch this place, that its beauty is fleeting.

(As an aside, many people think the “loss of innocence” in the chorus is the loss of the girl’s virginity, but frankly, I don’t see it. When the chorus says, “Just lay your head back on the ground/ and let your hair spill all around me,” I picture the two lying NEXT to each other. Moreover, if he were talking about the loss of the girl’s virginity, the “offer up your best defense” line would be unnecessarily menacing, as if the narrator is having sex with her against her will. Bottom line: this interpretation just doesn’t fit with the rest of the song.)

Henley and Hornsby have worked with other artists before and since: Henley with Stevie Nicks, Patty Smyth, and Axl Rose, Hornsby with Bonnie Raitt, Huey Lewis, and the Grateful Dead. But “The End of the Innocence” is a landmark collaboration, in that it truly is co-authored: Don didn’t merely lend his voice to a Bruce tune, and Bruce didn’t merely play piano on a Don tune. Instead, the two combined their talents to create one of the best songs of the decade. (Astoundingly, though, it only reached 99 — out of 100 — on the Billboard Year-End Chart for 1989. Are you kidding me with that?)

Author Marc Eliot calls “The End of the Innocence” as a “combination anthem and eulogy,” and for those of us who “came of age” during the 80s, the song really does serve as a eulogy of sorts. The lyrics talk about different “ends,” but now, after twenty-five years, the song can represent one more — the end of the 1980s.

Sure, the song came out in the summer (which meant six more months’ worth of songs came out after that). And sure, Henley himself is critical of the 80s in the song. And heck, the 80s weren’t really all that innocent (with the outbreak of AIDS and the Iran-Contra hearings and fear of global thermonuclear war).

But no matter. Nostalgia helps us overlook those blemishes, and those of us who lived through the 1980s will always remember it as a simpler, innocent time — a time of Pac-Man and parachute pants, of Rubik’s Cubes and role-playing games, of words and music.

August 15, 2016

Most of you wrote is great. But the brilliance of the song is that it is about all the stuff you wrote, AND poetically compared with the bittersweet loss of virginity, perhaps for both of them. He’s not having sex with her against her will, exactly, it’s just a evocative way of describing getting past the complicated emotional defenses that can hold a girl back from her first time having sex, even if she wants to very much.